Axel Merk, Merk Investments

February 12th, 2013

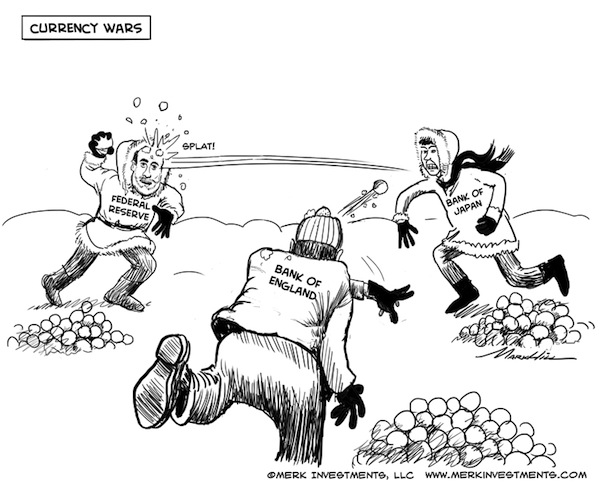

Real people may die when countries engage in “currency wars.” Countries debasing their currencies risk, amongst others:

- Loss of competitiveness

- Social unrest

- War

|

|---|

The illusory benefit of a weaker currency is to boost corporate earnings as companies increase their exports. That may well be true for the next quarterly earnings report, but ignores that their competitive position may be weakening. The clearest evidence of this is the increased vulnerability to takeovers from abroad. As the value of the U.S. dollar has been eroding, for example, Chinese companies are increasingly buying U.S. assets. The U.S. is selling its family silver in an effort to support consumption.

Importantly, when a country subsidizes one’s exports with an artificially weak currency, businesses lack an incentive to innovate. Japan is the best example: Japan’s problem is not that of a strong currency, but a lack of innovation. By weakening the yen, companies are given a free ride, taking an incentive away to engage in reform. Advanced economies, in our humble opinion, cannot compete on price, but must compete on value. European companies have long learned this, as there are rather few low-end consumer goods being exported from Germany. The Chinese have also heeded this lesson, allowing low-end industries to fail and relocate to Vietnam or other lower cost countries: China is rapidly moving up the value chain in goods and services produced. Incidentally, Vietnam has repeatedly engaged in currency devaluation, as the country mostly competes on price; in the absence of a strong consumer recovery in the U.S., we see further currency debasements in Vietnam.

In summary, market pressure to innovate is the most powerful motivation. Governments subsidizing ailing industries through currency debasement do long-term harm to their economies.

Social unrest

Currency debasement is not just bad for the corporate world: it’s particularly painful for citizens. Just ask citizens of Venezuela where the government just announced a 32 percent devaluation in the bolívar’s official exchange rate to the dollar. An overnight move of that magnitude is immediately noticeable, as are the negative effects on consumers, whereas gradual debasement in currencies of advanced economies are less noticeable, but ultimately have the same effect. The natural consequence of currency debasement is inflation, i.e., loss of real purchasing power; the two forces meet at the gas pump: as a currency loses value, commodities – all else equal – become pricier when valued in that currency.

Stagnant real wages in the U.S. over the past decade may in large part be attributed to the gradual debasement of the greenback, courtesy of fiscal and monetary policy. Folks whose real wages didn’t go anywhere for a decade feel cheated and are more likely to vote for populist politicians promising change. Currency debasement fosters growing income and wealth inequality and diverging political reactions, e.g., the Tea Party movement on the political right and the Occupy WallStreet movement on the political left. The rise of populism can be seen in the rise of Twitter: we sometimes quip that politicians that can distill their political message into a tweet have a better chance of being elected these days. Except that we are wrong: it’s not a joke.

In the Middle East, similar trends cause revolutions. People can be suppressed for a long time, but if they can’t feed themselves, they revolt. In the U.S., we are told food and energy are to be excluded from measuring inflation, as our economy is less and less dependent on food and energy (although curious that a record number of Americans used food stamps last year). However, in countries where large segments of the population cannot earn enough to feed themselves, currency debasement contributes to revolutions, not just the rise of populism.

For those that believe currency debasement is the appropriate way to escape a depression, keep in mind that the Great Depression provided a transition to World War II. Currency Wars fought in the first half of the 20th century tended to be a result of fiscal policy. For example, in 1925, the UK returned to the gold standard at pre World-War-I levels, although the UK could ill afford it. In 1931, Britain was forced to depart from the gold standard again. Japan suspended the gold standard in 1917, returned to it in early 1930, only to depart from it again in late 1931. In 1934, the U.S. dollar was devalued by 40% when an ounce of gold was officially priced at $35 an ounce, up from $20.67 an ounce. Exchange rates caught up with reality.

In today’s world, where major countries have free-floating exchange rates, monetary policies appear to be more pro-active rather than reactive. Either way, underlying fiscal or monetary policy have a profound impact on currency values, both in real (purchasing power) and relative (exchange rate) terms. Given unprecedented debt and deficit levels on the fiscal side, and aggressive central bank balance sheet expansion on the monetary side, we believe the term “currency war” is more than appropriate.

When told by Fed Chairman Bernanke that the gold standard prolonged the Great Depression, many feel as if monetary activism were a blessing rather than a curse. In our assessment, Ivory Tower economists are particularly apt at confusing cause and effect. The root causes of a depression are excessive debt, not currencies that are too strong. Currency debasement and expansionary monetary policies are attempts to socialize such debt, bailing out those that have taken on irresponsible debt burdens. But because governments tend to be in the group of those taking on excessive debt burdens, we are made to believe that such policy is for the greater good.

We respectfully disagree: currency wars destroy wealth. Currency wars have a disproportionate impact on the poor, as they don’t hold assets whose value is inflated in nominal terms and that could buffer some of the fallout. Central banks don’t cause real wars. But monetary policy has a profound impact on the social fabric. Abstract theories about how aggressive monetary action are the remedy to depressions ignores the heavy social toll currency wars have on people. For those that argue that the social toll of a depression is greater, we respond that the best short-term policy to address economic ills is a good long-term policy. We cannot see how currency wars can be good long-term policy.

What to do about Currency Wars

We can lament all we want, but ultimately, we are observers rather than instigators. We can be actors when it comes to our own wealth, seeking to protect it from the fallout of currency wars. We believe the best place to fight a currency war might be in the currency market itself, as there may be a direct translation from what we call the mania of policy makers into the currency markets. It’s not a zero-sum game, as different central banks print different amounts of money (that is, if one calls central bank balance sheet expansion money “printing”, even if no real currency is printed, but central banks purchase assets with fiat currency created on a keyboard). Equities may also rise when enough money is printed causing all asset prices to float higher, but one also takes on the “noise” of the equity markets: when no leverage is employed, equity markets are substantially more volatile than the currency markets.

Some call currency markets too difficult to understand. We happen to think that ten major currencies are much easier to understand than thousands of stocks. But nobody said it’s easy.

Calling it a race to the bottom does not give credit to what we believe are dramatically different cultures across the world. Gold may be the winner long-term, but for those who don’t have all their assets in gold, the question remains how to diversify beyond what we call the ultimate hard currency. To potentially profit from currency wars, one needs to project one’s view of what policy makers may be up to onto the currency space. And if there is one good thing to be said about our policy makers, it is that they may be rather predictable.

No comments:

Post a Comment