Monday, April 30, 2012

Sunday, April 29, 2012

Saturday, April 28, 2012

Friday, April 27, 2012

Jim Sinclair - Gold for Oil

|

The implications of China paying for Iranian oil in gold is the most important event in the modern history of gold

1. It is reasonable to assume that China has been threatened with total or at least selective exclusion from the SWIFT system if it pays in any currency for Iranian oil.

2. Gold has been decided by China as the means of making payment for massive international purchases free of the SWIFT system.

3. Other Asian and Middle Eastern nations will now see the gold they hold as money free of Western economic interference.

4. Gold now is not only money free of liability, but also free from interference regarding settlement by the long arm of Western influence.

5. The SWIFT system is becoming ever more a weapon of Western international political will.

6. In case of war anywhere, it is now demonstrated for all to see that only gold will buy the materials required. Paper currencies are under the SWIFT system's control in settlement.

7. Far from being a barbaric relic, gold is now clearly the money of state survival in every sense.

8. It is reasonable and possible for the supply of physical gold to fall far behind the size of the massive short positions now common to algorithm and hedge fund paper shorts. That will make an effective cover at a reasonable price as compared to a certain day's close impossible the following day on an exogenous event.

9. It may not be possible to use TA of any nature to determine a price of overvaluation for gold. Should the USA decide to take on China in full out economic war with the physical market totally illiquid, such as through isolation from the SWIFT system, consider the gold price that might result.

|

Labels:

Gold

Thursday, April 26, 2012

The Best Reason in the World to Buy Gold

Gordon G. Chang, Contributor

I write primarily on China, Asia, and nuclear proliferation.

4/22/2012 @ 5:05PM |12,564 views

On the last day of 2011, President Obama signed the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012. The NDAA, as it is called, attempts to reduce Iran’s revenue from the sale of petroleum by imposing sanctions on foreign financial institutions conducting transactions with Iranian financial institutions in connection with those sales. This provision, which essentially cuts off sanctioned institutions from the U.S. financial system, takes effect on June 28.

The NDAA gives the president the power to waive the sanctions depending on the availability and price of supplies from non-Iranian sources. He can also exempt financial institutions from countries that have significantly cut back purchases of Iranian petroleum. Last month, the State Department announced waivers for Japan and ten European countries. China, which has received American waivers in the past under other Iran legislation, is now Tehran’s largest oil customer and investor as well as its largest trading partner. Given the new mood in Washington, Beijing cannot count on getting more exceptions in the future.

The NDAA gives the president the power to waive the sanctions depending on the availability and price of supplies from non-Iranian sources. He can also exempt financial institutions from countries that have significantly cut back purchases of Iranian petroleum. Last month, the State Department announced waivers for Japan and ten European countries. China, which has received American waivers in the past under other Iran legislation, is now Tehran’s largest oil customer and investor as well as its largest trading partner. Given the new mood in Washington, Beijing cannot count on getting more exceptions in the future.

As the Wall Street Journal noted in early January, the sanctions are “an attempt to force other countries to choose between buying oil from Iran or being blocked from any dealings with the U.S. economy.” The strict measures put Chinese officials in a bind. They apparently believe their geopolitical interests align with those of Tehran, but their economy is becomingincreasingly reliant on America’s.

So how can Beijing keep both Iran’s ayatollahs and President Obama happy at the same time? Simple, the Chinese can avoid the U.S. sanctions through barter. China has already been trading its produce for Iran’s petroleum, but there is only so much gai lan and bok choy the Iranians can eat. That’s why Iran is also accepting, among other goods, Chinese washing machines, refrigerators, toys, clothes, cosmetics, and toiletries.

The barter trade works, but Iran needs cash too. As it is being cut off from the global financial system, the next best thing is gold. So we should not be surprised that in late February the Iranian central bank said it would accept that metal as payment for oil. Last year, China imported $21.7 billion in Iranian oil and exported $14.8 billion in goods and services. As the NDAA goes into effect, look for Beijing to ship gold to Iran to make up the difference.

Gold bugs, however, shouldn’t get too happy about Iran’s plight. There are five principal factors that will depress anticipated demand for gold used to buy Iranian oil. First, other countries will also be bartering agricultural and manufactured goods. Russia and Pakistan, for instance, will undoubtedly continue wheat-for-petroleum arrangements.

Second, Tehran, out of apparent desperation, in February said it would also accept local currencies, thereby avoiding the U.S. financial system. As a result, the Indians announced in January that they would not request a waiver from the Obama administration, and they began opening rupee accounts to pay for as much as 45% of their oil purchases with their currency. In 2011, India exported only $2.7 billion to Iran while buying $9.5 billion in oil. Similarly, the Chinese, smelling blood in the water, will surely press the Iranians to accept the non-convertible renminbi.

Third, the result of sanctions is that Iran’s oil exports could be cut by as much as 700,000 barrels a day. China, for instance, is increasing its oil purchases from Saudi Arabia, its largest foreign supplier. The Chinese are also buying more from the Persian Gulf emirates as well as Vietnam, Russia, and Africa. Of course, every drop of other crude decreases China’s demand for Iran’s.

Fourth, China and other countries are taking advantage of Iran’s plight by negotiating large price reductions.

Fifth, if the Iranians are willing to accept wheat and non-tradable currencies in payment for oil, there is nothing to say they won’t start agreeing to silver too.

But nothing shines like gold. And there is one other reason to be bullish on the yellow metal. “This isn’t the end of the road,” noted an unnamed senior administration official to the Wall Street Journal days after the enactment of the NDAA. “There are many other sanctions we can put in place and that our multilateral partners around the world can put in place and will be.” As Washington tightens financial measures against Iran, the mullahs will have less access to hard currency and therefore more need for gold.

Unless, of course, they want to accumulate more Chinese washing machines.

Unless, of course, they want to accumulate more Chinese washing machines.

I thank “straightarrow,” a reader of this column, for alerting me to this issue.

Follow me on Twitter @GordonGChang

Labels:

Gold

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

The Hidden Role of Gold at the IMF

April 23, 2012

...via USNews

James Rickards is a hedge fund manager in New York City and the author of Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisisfrom Portfolio/Penguin. Follow him on Twitter: @JamesGRickards.

The International Monetary Fund completed their spring meetings last weekend amid communiqués and good feelings about what had been accomplished. There was optimism about improvement in the global economy albeit tempered by warnings that risks remained. Christine Lagarde, the organization's managing director, was upbeat about new financing pledges to help build an IMF firewall to prevent contagion from countries in financial distress.

Yet, behind this facade of goodwill were stresses between the rising economic powers, notably Brazil, China, and India, and developed economies in Europe. In the middle of these stresses is the United States, which is the only country in the world with veto power over IMF decisions. To understand what is driving the International Monetary Fund today, it is necessary to look behind the jargon of the communiqués and examine the hardball politics actually playing out. These politics involve the U.S. response to the firewall, the relative voting rights of IMF members, and the hidden role of gold.

The most urgent task at the organization today is the construction of a financial firewall that can be used to lend to countries in distress to prevent a default and worldwide panic of the type that emerged in 2008. The most likely country to need this kind of help is Spain, although some assistance to Italy cannot be ruled out. The International Monetary Fund builds the firewall by obtaining commitments to lend from its member countries. The commitments can then be converted to cash quickly by sending a borrowing notice to the lender—something like drawing on a line of credit at your bank.

The United States committed about $100 billion to this effort in 2009. However, the United States is making it clear behind the scenes that it is not willing to fund that commitment now, and it can use its veto power to stop a borrowing notice if necessary. This is causing problems with other lenders such as China and Brazil who may only be willing to lend if the United States does likewise.

The United States justifies its reluctance publicly by saying that Europe needs to do more to finance its own bailout. In fact, the reasons the United States will not lend are purely political. A loan to the International Monetary Fund is a toxic election issue for President Obama. One can hear Republican opponents gleefully asking why U.S. taxpayer money is being used to bail out Greeks who take retirement and hit the beach at age 50 while Americans work well into their 60s or older because they cannot afford to retire. The financial fate of Europe and the world now hinges on the U.S. election calendar. We'll see if Europe makes it to November without the kind of panic that would require Obama to reverse course.

The second big issue at the International Monetary Fund involves the voting rights of the emerging economies. In this area, sore spots abound. One supposedly egregious example involves the comparison of Belgium and Brazil. Brazil's economy is five times the size of Belgium's. Yet, Belgium has more IMF votes than Brazil giving Belgium a slightly larger voice. Many examples of this type exist. The cumulative effect is that Europe as a whole is over-represented relative to the emerging economies. The fact that a European leads the International Monetary Fund adds insult to injury for some.

This highlights the most interesting but least discussed aspect of the international monetary system—the hidden role of gold. The organization itself has the third largest gold hoard in the world, over 2,800 tons, just behind the United States and Germany. It's interesting that the International Monetary Fund still has this much gold since it officially stopped counting gold as an international reserve asset in 1973. However, individual nations continue to include gold in their reserves for internal purposes.

This brings us back to the curious case of Belgium. Its gross domestic product may be only 20 percent of Brazil's, but it has almost seven times as much gold—Belgium has over 225 tons and Brazil has only about 33 tons. Indeed the countries that use the euro have a combined gold hoard of over 10,000 tons. This is more that the United States and more than Brazil, India, China, and Russia combined.

Paper currencies issued by Brazil and China that are backed by scant gold reserves are just paper. But currencies such as the dollar and the euro that are potentially backed by huge gold reserves are something more. The dollar and euro may be paper currencies today, but in a crisis the issuers have the ability to use gold backing on an emergency basis—an ability that other currencies lack. The International Monetary Fund has its owncurrency, the Special Drawing Right that can also be backed by gold in a crisis.

Despite decades of disparagement by mainstream economists gold is still the hidden hand of international finance. This is something that no finance minister or central banker will admit publicly because the implications for the leveraged paper money world are daunting. Yet actions and facts speak more loudly than words.Gold still determines who runs the system and who does not. China and Brazil will get their IMF votes—once they get their gold.

...via USNews bit.ly/IhziqI

Labels:

Central Banks,

Gold

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Monday, April 23, 2012

The unwitting move towards a global gold standard

Posted by Izabella Kaminska on Apr 23 12:39.

Professor Lew Spellman, from the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin, has an interesting new post out on the changing role of gold in the global economy.

It relates to the notion that a shortage of safe assets may be driving an epic hunt for “safe collateral” — driving down yields on traditional fixed-income investments — because there are more debt liabilities/obligations than safe collateral in the system.

In a zero-yielding environment like this, he believes gold begins to look remarkably attractive. This is especially the case if gold remains a liquid store of value, which is widely accepted as collateral across the system. What’s more, there’s little todifferentiate it from a zero-yielding Treasury bond. In fact, the Treasury bond eventually expires, while gold doesn’t.

As Spellman explains:

Hence, the great corollary of over indebtedness is the relative scarcity of good collateral to support the debt load outstanding. This imbalance of debt to collateral is impacting the ability of banks to make loans to their customers, for central banks to make loans to commercial banks, and for shadow banks to be funded by the overnight Repo market. Hence the growth of gold as a collateral asset to debt heavy markets is inevitably in the cards and is de facto occurring. Gold is stepping up to the plate as “good” collateral in a world of bad collateral.

What does this tell us about what’s happening to the global financial system?

In Spellman’s opinion, it seems to indicate that the market may unwittingly be moving towards a collateral-backed global currency (of its own accord). Possibly, even, a new gold standard altogether:

What we are witnessing is a sea change in which market forces are driving a de facto return to the gold standard. All that is missing for this to be a de jure gold standard is some regulatory and legal recognition and one has been proposed. The Basel Committee for Bank Supervision, the maker of global capital requirements is studying making gold a bank capital Tier 1 asset.

Which foretells the following for gold:

The world has gravitated from one gold-backed paper currency to another before, and it likely is happening again. It would depend on whether investors in liquid, default-free, inflation-free paper prefer gold-backed Chinese Yuan to Swiss warehouse receipts or deposits from large international banks with large gold positions that operate with lots of leverage. This is a market choice that will determine the gold linked paper store of value, but the point is that all the paper contenders derive value from the gold backing, and thereby expands the demand for the shiny metal. This is the new calculus of gold. This state of affairs is likely to remain until developed world governments no longer reach for the unreachable and pressure their central banks to finance it.

At FT Alphaville we’ve played around with the idea of a global mind-meld towards the re-collateralisation of the system’s liabilities before. It’s a theory that we would say explains a lot. Though the best way to think about it really is like a giant game of musical chairs. While the music is playing, nobody cares about there being a lack of chairs. Probability wise, the impression is that almost everyone will be able to get a chair if and when the music stops.

But what happens when the music stops and there are far fewer chairs than anyone expected…? (And when the probability of winding up with no chair next time round is much higher than originally expected?) In that scenario participants begin to “eye” their potential seats ever more closely. Anyone with a stake in the game might even choose to reserve a seat by paying off fellow participants.

That process of reserving a seat thus echoes the collateralisation that’s going on today. Collateralisation equals the location and identification of real-world assets against which existing financial claims can be satisfied. If there’s a lack of acceptable assets in the system versus outstanding claims — the stakes in the financial version of musical chairs rise significantly. As does the cost of reserving a seat, a fact which manifests in the real world as negative yields.

See why ‘the debt-to-safe asset ratio’ may be worth paying attention to?

http://on.ft.com/JJUl6a

Labels:

Central Banks,

Currency Wars,

Gold

Sunday, April 22, 2012

Jeremy Grantham's 10 Investment Lessons

1. Believe in history: "history repeats and repeats, and forget it at your peril. All bubbles break, all investment frenzies pass away."

2. Neither a lender nor a borrower be: "Unleveraged portfolios cannot be stopped out, leveraged portfolios can. Leverage reduces the investor's critical asset: patience."

3. Don't put all your treasure in one boat: "This is about as obvious as any investment advice could be ... Several different investments, the more the merrier, will give your portfolio resilience, the ability to withstand shocks."

4. Be patient and focus on the long term: Wait for the good cards. If you've waited and waited some more until finally a very cheap market appears, this will be your margin of safety."

5. Recognize your advantages over the professionals: "The individual is far better-positioned to wait patiently for the right pitch while paying no regard to what others are doing, which is almost impossible for professionals."

6. Try to contain natural optimism: "optimism comes with a downside, especially for investors: optimists don't like to hear bad news."

7. But on rare occasions, try hard to be brave: "You can make bigger bets than professionals can when extreme opportunities present themselves because, for them, the biggest risk that comes from temporary setbacks - extreme loss of clients and business - does not exist for you."

8. Resist the crowd, cherish numbers only: "this is the hardest advice to take: the enthusiasm of a crowd is hard to resist. The best way to resist is to do your own simple measurements of value, or find a reliable source (and check their calculations from time to time) ... and try to ignore everything else."

9. In the end it's quite simple, really: "GMO predicts asset class returns in a simple and apparently robust way: we assume profit margins and price earnings ratios will move back to long-term average in 7 years from whatever level they are today. We have done this since 1994 and have completed 40 quarterly forecasts ... Well, we have won all 40."

10. This above all, to thine own self be true: "To be at all effective investing as an individual, it is utterly imperative that you know your limitations as well as your strengths and weaknesses ... you must know your pain and patience thresholds accurately and not play over your head. If you cannot resist temptation, you absolutely must not manage your own money."

Grantham elaborates on each lesson and address other topics in his full quarterly letter,

Saturday, April 21, 2012

Friday, April 20, 2012

Currency Wars: Gambling With Other Peoples’ Money

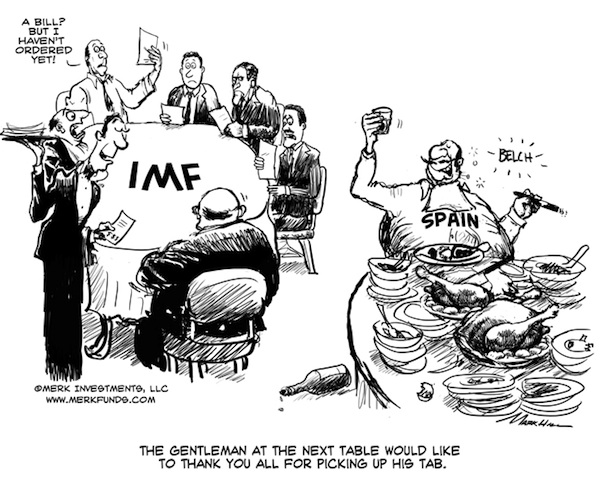

Axel Merk, Merk Funds

April 19, 2012

If running out of your own money wasn’t bad enough, policy makers are increasingly spending other peoples’ money to bail their country out. At the upcoming G-20 meeting, finance ministers from around the world will contemplate an increase to the resources of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). At stake for politicians is whether they can continue to do what they know best – to play politics. In contrast, at stake for investors may be whether currencies will retain their function as a store of value.

|

Let’s highlight Spain, as the country may be the key to understanding how dynamics may play out. Last November, Spaniards voted for change by electing conservative Prime Minister Rajoy, handing him an absolute majority in parliament, displacing the previous, socialist government. The election may cause former British Prime Minister Thatcher to change her view, that socialism is doomed to fail, as ultimately you run out of other people’s money. It doesn’t take a socialist to run out of money. In the case of Spain, if you run out of your own people’s money, there may always be other peoples’ money.

One of the major concerns is Spain's regional government debt. Spain consists of 17 autonomous regions, whose total debt almost doubled in the past three years, due to economic recession and a housing market collapse. In many ways, Spain reflects a microcosm of how the Eurozone as a whole is structured:

- Spanish regions have the power to issue public debt. The central government has little ability to interfere with regional government spending and is prohibited by Spanish law to bailout regional governments.

- While regions enjoy high autonomy on spending, the central government retains effective control over regional government revenue.

- Spain has its own peripheral problems: the most indebted region, Catalonia, recorded 20.7% debt-to-regional-GDP ratio and 3.6% deficit-to-GDP ratio in 2011. Its 10-year bond yield recently breached 10%, far beyond the yield on 10-year Spanish government bonds, which yield around 6%. In 2011, the total debt of 17 regional governments rose to €140 billion, accounting for 13.1% of Spain's GDP. This number is up from 6.7% by 2008.

- Spanish law forbids the central government from rescuing regional governments (in much the same way that the Maastricht Treaty prohibits bailouts of EU countries). In practice, the central government appears to have implicitly helped Valencia, Spain’s 2nd most indebted region, with a €123 million loan repayment to Deutsche Bank.

The tensions between Spanish regions and its national government are nothing new. And that’s really the main lesson here: it’s business as usual in Spain! As of late, Rajoy’s government appears to be reining in regional control over budgets in earnest. However, Spaniards are used to eternal debates on where subsidies should come from, how to stop regions from spending, and – conversely - how to find ways around restrictions. In brief, Spaniards are pros at this battle. Not surprisingly, when there’s a threat of market headwinds, Rajoy is publicly committing to reform. The moment the pressure abates, it appears those promises are forgotten. Spain is proof that the only language policy makers may be listening to is that of the bond market.

As painful as it is, volatile markets are necessary to keep policy makers focused. Whenever Spanish bonds come under pressure, Spain moves further from talk and closer to action, with respect to implementation of more austerity measures, as well as the pursuit of structural reforms. Spain – like so many developed countries – has rigid bureaucracies aimed at protecting the old (companies and employees) at the cost of preventing the new, stifling innovation and fostering massive youth unemployment. Structural reform is politically painful. What is striking about Spain is that it has an enviable position of a government with an absolute majority. Yet, even such a seemingly strong government is dragging its feet in implementing reform. In the process, political support is eroding, thus making it increasingly difficult to pursue reforms as the economic environment worsens.

Politicians always appear to consider the cost of acting versus the cost of inaction. As long as more money is lined up: be that from the central government for the regions; be that from a European stability fund for the government; or be it from the IMF, incentives for reforms are taken away. In many ways, Catalonia should be getting the message that its budget is unsustainable, but with help on the way from Madrid, the region may continue its bad habits.

As Europeans have convinced themselves that they have done plenty of the heavy lifting, the next stop is the IMF, where member countries are expected to pledge billions more. The critics may be forgiven for pointing out that Europe could be doing more before tapping into purses of other, less affluent countries. Unfortunately, politicians treat this as politics rather than a serious debate about money. The good news here may be that we don’t think this is a European problem. The bad news is that this is a global problem. Spain is not unique. In the U.S., we have many of the same challenges, but we have a bond market that has allowed policy makers to get away with spending ever more money. Different from the Eurozone, the U.S. has a significant current account deficit. As such, should the bond market impose austerity on U.S. policy makers, it may have far more negative implications on the U.S. dollar than it has had on the Euro to date.

In the meantime, as policy makers around the world continue to hope for the best, but plan for the worst, expect monetary policy to be most accommodating: the U.S., Eurozone, UK and Japan all have eased in some form or another in recent months. Beneficiaries in the medium term may be precious metals and commodity currencies. For now, those currencies have been held back by a generally somber mood about global growth. What has done well – and we expect will continue to do well – are the currencies of countries that realize such policies will foster inflationary pressures. Singapore should be praised in this context, as the Singapore Monetary Authority tightened monetary policy last week, allowing the Singapore Dollar to appreciate. Those countries that can afford to are taking note that all this easy money may have significant side effects and are taking action to combat it. However, such countries are few and far between. We have long argued that there may not be such a thing anymore as a safe asset and investors may want to take a diversified approach to something as mundane as cash.

Labels:

Central Banks,

Economy

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)