Axel Merk, Merk Funds

April 19, 2012

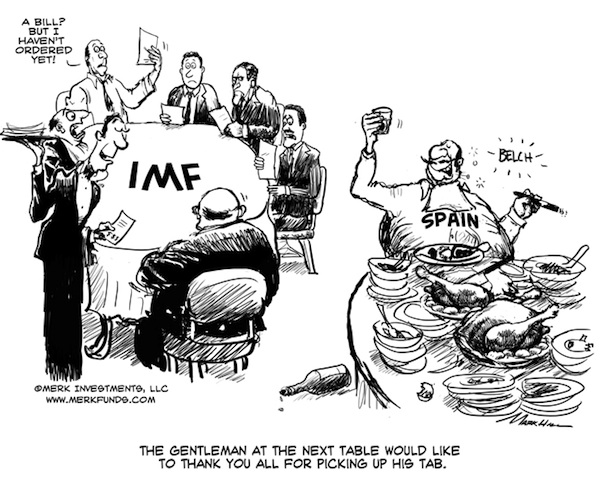

If running out of your own money wasn’t bad enough, policy makers are increasingly spending other peoples’ money to bail their country out. At the upcoming G-20 meeting, finance ministers from around the world will contemplate an increase to the resources of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). At stake for politicians is whether they can continue to do what they know best – to play politics. In contrast, at stake for investors may be whether currencies will retain their function as a store of value.

|

Let’s highlight Spain, as the country may be the key to understanding how dynamics may play out. Last November, Spaniards voted for change by electing conservative Prime Minister Rajoy, handing him an absolute majority in parliament, displacing the previous, socialist government. The election may cause former British Prime Minister Thatcher to change her view, that socialism is doomed to fail, as ultimately you run out of other people’s money. It doesn’t take a socialist to run out of money. In the case of Spain, if you run out of your own people’s money, there may always be other peoples’ money.

One of the major concerns is Spain's regional government debt. Spain consists of 17 autonomous regions, whose total debt almost doubled in the past three years, due to economic recession and a housing market collapse. In many ways, Spain reflects a microcosm of how the Eurozone as a whole is structured:

- Spanish regions have the power to issue public debt. The central government has little ability to interfere with regional government spending and is prohibited by Spanish law to bailout regional governments.

- While regions enjoy high autonomy on spending, the central government retains effective control over regional government revenue.

- Spain has its own peripheral problems: the most indebted region, Catalonia, recorded 20.7% debt-to-regional-GDP ratio and 3.6% deficit-to-GDP ratio in 2011. Its 10-year bond yield recently breached 10%, far beyond the yield on 10-year Spanish government bonds, which yield around 6%. In 2011, the total debt of 17 regional governments rose to €140 billion, accounting for 13.1% of Spain's GDP. This number is up from 6.7% by 2008.

- Spanish law forbids the central government from rescuing regional governments (in much the same way that the Maastricht Treaty prohibits bailouts of EU countries). In practice, the central government appears to have implicitly helped Valencia, Spain’s 2nd most indebted region, with a €123 million loan repayment to Deutsche Bank.

The tensions between Spanish regions and its national government are nothing new. And that’s really the main lesson here: it’s business as usual in Spain! As of late, Rajoy’s government appears to be reining in regional control over budgets in earnest. However, Spaniards are used to eternal debates on where subsidies should come from, how to stop regions from spending, and – conversely - how to find ways around restrictions. In brief, Spaniards are pros at this battle. Not surprisingly, when there’s a threat of market headwinds, Rajoy is publicly committing to reform. The moment the pressure abates, it appears those promises are forgotten. Spain is proof that the only language policy makers may be listening to is that of the bond market.

As painful as it is, volatile markets are necessary to keep policy makers focused. Whenever Spanish bonds come under pressure, Spain moves further from talk and closer to action, with respect to implementation of more austerity measures, as well as the pursuit of structural reforms. Spain – like so many developed countries – has rigid bureaucracies aimed at protecting the old (companies and employees) at the cost of preventing the new, stifling innovation and fostering massive youth unemployment. Structural reform is politically painful. What is striking about Spain is that it has an enviable position of a government with an absolute majority. Yet, even such a seemingly strong government is dragging its feet in implementing reform. In the process, political support is eroding, thus making it increasingly difficult to pursue reforms as the economic environment worsens.

Politicians always appear to consider the cost of acting versus the cost of inaction. As long as more money is lined up: be that from the central government for the regions; be that from a European stability fund for the government; or be it from the IMF, incentives for reforms are taken away. In many ways, Catalonia should be getting the message that its budget is unsustainable, but with help on the way from Madrid, the region may continue its bad habits.

As Europeans have convinced themselves that they have done plenty of the heavy lifting, the next stop is the IMF, where member countries are expected to pledge billions more. The critics may be forgiven for pointing out that Europe could be doing more before tapping into purses of other, less affluent countries. Unfortunately, politicians treat this as politics rather than a serious debate about money. The good news here may be that we don’t think this is a European problem. The bad news is that this is a global problem. Spain is not unique. In the U.S., we have many of the same challenges, but we have a bond market that has allowed policy makers to get away with spending ever more money. Different from the Eurozone, the U.S. has a significant current account deficit. As such, should the bond market impose austerity on U.S. policy makers, it may have far more negative implications on the U.S. dollar than it has had on the Euro to date.

In the meantime, as policy makers around the world continue to hope for the best, but plan for the worst, expect monetary policy to be most accommodating: the U.S., Eurozone, UK and Japan all have eased in some form or another in recent months. Beneficiaries in the medium term may be precious metals and commodity currencies. For now, those currencies have been held back by a generally somber mood about global growth. What has done well – and we expect will continue to do well – are the currencies of countries that realize such policies will foster inflationary pressures. Singapore should be praised in this context, as the Singapore Monetary Authority tightened monetary policy last week, allowing the Singapore Dollar to appreciate. Those countries that can afford to are taking note that all this easy money may have significant side effects and are taking action to combat it. However, such countries are few and far between. We have long argued that there may not be such a thing anymore as a safe asset and investors may want to take a diversified approach to something as mundane as cash.

No comments:

Post a Comment