Thursday, February 28, 2013

Pierre-August Renoir, 1915

http://www.openculture.com/2013/02/iconic_artists_at_work_watch_rare_videos_of_picasso_matisse_kandinsky_renoir_monet_and_more.html

Labels:

art and architecture,

life,

philosophy

Tuesday, February 26, 2013

Sunday, February 24, 2013

Jesse Livermore’s Trading Rules Written in 1940

- Nothing new ever occurs in the business of speculating or investing in securities and commodities.

- Money cannot consistently be made trading every day or every week during the year.

- Don’t trust your own opinion and back your judgment until the action of the market itself confirms your opinion.

- Markets are never wrong – opinions often are.

- The real money made in speculating has been in commitments showing in profit right from the start.

- At long as a stock is acting right, and the market is right, do not be in a hurry to take profits.

- One should never permit speculative ventures to run into investments.

- The money lost by speculation alone is small compared with the gigantic sums lost by so-called investors who have let their investments ride.

- Never buy a stock because it has had a big decline from its previous high.

- Never sell a stock because it seems high-priced.

- I become a buyer as soon as a stock makes a new high on its movement after having had a normal reaction.

- Never average losses.

- The human side of every person is the greatest enemy of the average investor or speculator.

- Wishful thinking must be banished.

- Big movements take time to develop.

- It is not good to be too curious about all the reasons behind price movements.

- It is much easier to watch a few than many.

- If you cannot make money out of the leading active issues, you are not going to make money out of the stock market as a whole.

- The leaders of today may not be the leaders of two years from now.

- Do not become completely bearish or bullish on the whole market because one stock in some particular group has plainly reversed its course from the general trend.

- Few people ever make money on tips. Beware of inside information. If there was easy money lying around, no one would be forcing it into your pocket.

chapeau Mr. Saut... http://www.raymondjames.com/inv_strat.htm

Friday, February 22, 2013

Claude Monet, 1915

http://www.openculture.com/2013/02/iconic_artists_at_work_watch_rare_videos_of_picasso_matisse_kandinsky_renoir_monet_and_more.html

Labels:

art and architecture,

life,

philosophy

Thursday, February 21, 2013

...from Dr John - No, Not Again

"The chart above features two brackets. The first depicts a run-of-the-mill market decline of 32%, which is the historical average of how market cycles are completed. Such a decline would wipe out more than half of the recent bull market advance. The second bracket depicts a 39% bear market decline, which is the historical average for cyclical bear markets that take place within secular bear market periods.

In recent weeks, market conditions have established an overvalued, overbought, overbullish, rising-yield syndrome in a mature bull market; conditions that uniquely marked the peaks of advances in 1929, 1972, 1987, 2000, 2007, and 2011 (see A Reluctant Bear’s Guide to the Universe). The instance in 2011 preceded a forgettable market decline near 20%. The other points represent a Who’s Who of tops preceding the most violent market losses in history – even if the most severe outcomes were not immediate. While the 1987 and 2000 instances coincided with the exact market peaks, the average lead time to the market’s ultimate peak was about 4 weeks, and in 2011 took as long as 15 weeks. In every case but 2011, the market peak was within 3% of the point that this syndrome emerged, with the largest gain being a 6% advance observed in the 2011 instance. It is impossible to know whether the recent advance will remain within these prior ranges. The record-high of the S&P 500 was 1565 on October 9, 2007, and that level is only a few percent away. With sentiment already ebullient on nearly every objective measure, a new market high would put a cherry on top, and that should not be ruled out."

http://www.hussman.net/wmc/wmc130218.htm

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Kyle Bass Japan

Labels:

Central Banks,

civil unrest,

Economy,

GIB

Tuesday, February 19, 2013

Sunday, February 17, 2013

Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There

Jeffrey Saut

February 11, 2013

“Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There” is the title of a book written by Sylvia Boorstein. I was reminded of the title when I received the following email from a financial advisor at another firm last week:

“Hey Jeff, not only do my clients want me to ‘do something,’ now I am starting to get the feeling I should do something. My shopping list of stocks to buy for the ‘consolidation-pullback’ is up 20%+ over the past five weeks, yet I have not bought any of them despite the fact I have plenty of cash on the sidelines. Now, the next pullback should be higher than where I started waiting for a pullback two weeks ago. For my active accounts, I’ve actually raised a little cash on every step to the upside, but have been holding back on that strategy this week. When my clients start calling ME to talk about what stocks to buy it makes me nervous and I start to get more cautious. Please remind me not to dosomething just to do something, to be patient. Regrettably, I’m starting to feel like an underperforming hedge fund manager.”

It is typical to hear such laments at this stage of a “buying stampede” as the outswant to be in for the presumed next leg of the rally. Unfortunately, today is session 28 in the typical 17- to 25-session duration of a “buying stampede.” As stated last Monday:

“Such skeins only have one- to three-session pauses or pullbacks before they exhaust themselves on the upside. While a few have lasted for 25 – 30 sessions, it is very rare to have one last for more than 30 sessions. That said, this one feels like it will extend toward the State of the Union address slated for February 12th. That address will likely be viewed negatively by the equity markets, which should serve to finally bring about a 5-7% correction. How the stock market reacts following such a pullback will tell us a lot about the market’s future direction.”

Indeed, I have written that if I could script what the markets were going to do it would be for the D-J Industrial Average (INDU/13992.97) to confirm the D-J Transportation Average’s breakout to new all-time highs with a new all-time closing high of its own. That would require the Dow to travel above its October 9, 2007 high of 14164.53, which is only 171.56 points away. If that happens, it would break the stock market out of its 13-year wide-swinging trading range, much like what occurred in August of 1982 following that 17+ year wide-swinging trading range market so often referenced in these missives. Likewise, it would clear up any doubts about a Dow Theory “buy signal.” Such an upside confirmation would also reinforce my sense that we are potentially in a new secular bull market.

With the thought of a new secular bull market in mind, I went back and studied my notes from August through November of 1982, which was the “lift-off” phase of a new secular bull market that would last until the spring of 2000. Accordingly, the sideways, wide-swinging stock market of 1965 – 1982 ended on August 9, 1982 with the Dow at 780.34. From there it went into a 20-session “buying stampede” that would leave the senior index 18.5% higher before peaking at 925.13 with a subsequent 3.7% pullback lasting 20 sessions. The second leg of the “lift-off” phase began on September 30, 1982 and took the Dow up another 14.7% where it challenged the then all-time high of 1051.70 made in January of 1973, coincident with the peaking of the nifty-fifty stocks. The Dow did not make it through that level on its first try, but after regrouping for seven sessions, the upside breakout was complete and the rest of the story is history, as can be seen in the chart on page 3.

Fast forward, the INDU bottomed on November 15, 2012 and marched higher into its mid-December short-term peak for a 5.66% gain. The ensuing decline was only 2.7% before the back-to-back 90% Upside Volume Days of December 31 and January 2, 2013 that started this year’s “buying stampede.” As of last Friday said stampede has lifted the Dow another 8.2%. The combined ride from November 2012’s intraday “lows” to the recent intraday “highs” has been 12.4%. Like in 1982, this two-step rise has left the Industrials and the S&P 500 (SPX/1517.93) within striking distance of their respective all-time highs. Whether they get through them on the first try remains to be seen, but many of the other indices have already done so. Yet, none of this really speaks to my emailer’s question about “doing something.”

To that point, I continue to like the strategy espoused by my friends at the Riverfront organization. To wit:

“First, identify the quantity of cash to be put to work – example: 20%. Second, break the trade into digestible chunks – example: break it into four parts, 5% each. Third, implement the first trade today – example: invest 5% into equities today. Fourth, set a date for implementing the second trade – example: two months from today invest the second 5%. Fifth, implement third and fourth segments if the market pulls back – example: invest the remaining 10% of the cash on market pullbacks. And six, after the date of the second trade occurs, return to step one with the remaining cash – example: two months from today, if the market never provides the opportunity to buy on a pullback, break the remaining 10% up into three to four parts and follow a strategy similar to the one utilized for investing the first 10%.”

As for what to buy, a few of the equity-centric mutual funds I own, and know and talk to the portfolio managers, are: GaveKal Knowledge Leaders (GAVAX/$12.33); Goldman Sachs Dividend Growth (GSRAX/$16.24); Hennessy Small Capitalization Financial (HSFNX/$21.53); Lord Abbett Growth Leaders (LGLAX/$16.58); MFS International Diversification (MDIDX/$14.64); and Putnam Capital Spectrum (PVSAX/$28.18). As for individual stocks, I would point you to our Analyst Current Favorites list, which can be retrieved by contacting your financial advisor.

The call for this week: Well, here we are with tomorrow night’s State of the Union address. Consequently, I am looking for a trading top this week follow by a 5% - 7% pullback and then we’ll see how the markets handle themselves. Again, if I could script it, I would like to see the Dow Industrials confirm the Dow Transports with a new all-time high of their own, which would use up all the stock market’s remaining internal energy on a short-term basis, resulting in a “sell on the news” pullback. However, they don’t operate the various markets for my benefit.

http://www.raymondjames.com/inv_strat.htm

Saturday, February 16, 2013

Quote Stuffing - Nanex

Nanex Research

That summer, Zero Hedge (Durden), USA Today (Krantz), CNBC (Pisani), Reuters (Lash), Barrons (McTague), the Wall Street Journal (Strausberg & Lauricella), the New York Times (Bowley), theAtlantic (Madigral), Risk Magazine (Wood), Bloomberg (Mehta) Bloomberg Magazine (Foroohar) and others investigated Quote Stuffing and asked the regulators (Trading and Markets Division at SEC) and the exchanges about it. The regulators and exchanges vehemently denied that Quote Stuffing existed and that we (Nanex) were conspiracy theorists. We have had many discussions with reporters who told us privately the language used was far from tame. And we are not even listing the reporters or news organizations that passed on writing a story because of what they were told by the regulators.

More recently, in October 2012, at a meeting between the SEC's Trading and Markets Division and major players from the Institutional buy-side, an SEC spokesperson besmirched Nanex's reputation with the same party line: that our research and findings were the stuff of conspiracy theory. So it is not surprising that respected and established media reporters who work closely with the street, and talk to them daily as colleagues, may have found our theories and graphics "out there". It is not surprising that quote stuffing and "bad algos" would be hard to believe and buy into unless you worked with market data every day.

Here are a few possibilities:

Credit Suisse: HFT DETECTION

Nanex Research

Inquiries: pr@nanex.net

Nanex ~ 14-Dec-2012 ~ Quote Stuffing Bombshell

Background

In June 2010, while analyzing the Flash Crash, we noticed that many stocks had extremely high rates of canceled orders (1000+ per stock, per second). We then looked at data back to 2004 and found hundreds of thousands of examples: the first beginning in July 2007, which not coincidentally is when High Frequency Trading (HFT) began exploiting the flaws of Reg. NMS. In our first published report on the Flash Crash, we came up with a term to describe this anomaly and coined Quote Stuffing. Two years later, we created the animation Rise of the Machines to chronicle the growth of this phenomenon.That summer, Zero Hedge (Durden), USA Today (Krantz), CNBC (Pisani), Reuters (Lash), Barrons (McTague), the Wall Street Journal (Strausberg & Lauricella), the New York Times (Bowley), theAtlantic (Madigral), Risk Magazine (Wood), Bloomberg (Mehta) Bloomberg Magazine (Foroohar) and others investigated Quote Stuffing and asked the regulators (Trading and Markets Division at SEC) and the exchanges about it. The regulators and exchanges vehemently denied that Quote Stuffing existed and that we (Nanex) were conspiracy theorists. We have had many discussions with reporters who told us privately the language used was far from tame. And we are not even listing the reporters or news organizations that passed on writing a story because of what they were told by the regulators.

More recently, in October 2012, at a meeting between the SEC's Trading and Markets Division and major players from the Institutional buy-side, an SEC spokesperson besmirched Nanex's reputation with the same party line: that our research and findings were the stuff of conspiracy theory. So it is not surprising that respected and established media reporters who work closely with the street, and talk to them daily as colleagues, may have found our theories and graphics "out there". It is not surprising that quote stuffing and "bad algos" would be hard to believe and buy into unless you worked with market data every day.

Credit Suisse Bombshell

Now comes along this paper (see below) from Credit Suisse, one of the global leaders in electronic trading and research. This paper describes Quote Stuffing as a strategy employed by HFT. Note that the termQuote Stuffing did not exist until we coined it in June 2010. Credit Suisse's paper shows how easy it is to detect. And that is true, it is that simple to spot and it continues to occur. Which is why the last 2 years have been confusing and frustrating to no end.Conclusion

With abundant evidence to the contrary, why would SEC Regulators deny that Quote Stuffing exists and that our analyses are "the stuff of conspiracy theories"? We are not about to engage in conspiracy theory talk now by saying someone is being paid or compensated to shill for HFT/Wall Street and putting the reputation and authority of the regulators at risk.Here are a few possibilities:

- The regulators don't wish to acknowledge that the playground they created has been taken over and exploited.

- They don't want to acknowledge their role as enablers.

- They have been working too closely with industry insiders in creating this playground, and now rely on the foxes for advice on how to safeguard the hen-house.

- Lobbyists hired by HFT firms and exchanges are very good at their job.

Credit Suisse: HFT DETECTION

Nanex Research

Inquiries: pr@nanex.net

Friday, February 15, 2013

Thursday, February 14, 2013

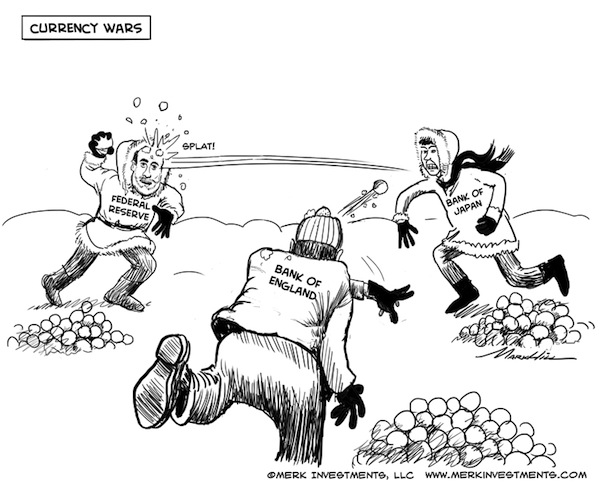

Currency Wars

Axel Merk, Merk Investments

February 12th, 2013

Real people may die when countries engage in “currency wars.” Countries debasing their currencies risk, amongst others:

- Loss of competitiveness

- Social unrest

- War

|

|---|

The illusory benefit of a weaker currency is to boost corporate earnings as companies increase their exports. That may well be true for the next quarterly earnings report, but ignores that their competitive position may be weakening. The clearest evidence of this is the increased vulnerability to takeovers from abroad. As the value of the U.S. dollar has been eroding, for example, Chinese companies are increasingly buying U.S. assets. The U.S. is selling its family silver in an effort to support consumption.

Importantly, when a country subsidizes one’s exports with an artificially weak currency, businesses lack an incentive to innovate. Japan is the best example: Japan’s problem is not that of a strong currency, but a lack of innovation. By weakening the yen, companies are given a free ride, taking an incentive away to engage in reform. Advanced economies, in our humble opinion, cannot compete on price, but must compete on value. European companies have long learned this, as there are rather few low-end consumer goods being exported from Germany. The Chinese have also heeded this lesson, allowing low-end industries to fail and relocate to Vietnam or other lower cost countries: China is rapidly moving up the value chain in goods and services produced. Incidentally, Vietnam has repeatedly engaged in currency devaluation, as the country mostly competes on price; in the absence of a strong consumer recovery in the U.S., we see further currency debasements in Vietnam.

In summary, market pressure to innovate is the most powerful motivation. Governments subsidizing ailing industries through currency debasement do long-term harm to their economies.

Social unrest

Currency debasement is not just bad for the corporate world: it’s particularly painful for citizens. Just ask citizens of Venezuela where the government just announced a 32 percent devaluation in the bolívar’s official exchange rate to the dollar. An overnight move of that magnitude is immediately noticeable, as are the negative effects on consumers, whereas gradual debasement in currencies of advanced economies are less noticeable, but ultimately have the same effect. The natural consequence of currency debasement is inflation, i.e., loss of real purchasing power; the two forces meet at the gas pump: as a currency loses value, commodities – all else equal – become pricier when valued in that currency.

Stagnant real wages in the U.S. over the past decade may in large part be attributed to the gradual debasement of the greenback, courtesy of fiscal and monetary policy. Folks whose real wages didn’t go anywhere for a decade feel cheated and are more likely to vote for populist politicians promising change. Currency debasement fosters growing income and wealth inequality and diverging political reactions, e.g., the Tea Party movement on the political right and the Occupy WallStreet movement on the political left. The rise of populism can be seen in the rise of Twitter: we sometimes quip that politicians that can distill their political message into a tweet have a better chance of being elected these days. Except that we are wrong: it’s not a joke.

In the Middle East, similar trends cause revolutions. People can be suppressed for a long time, but if they can’t feed themselves, they revolt. In the U.S., we are told food and energy are to be excluded from measuring inflation, as our economy is less and less dependent on food and energy (although curious that a record number of Americans used food stamps last year). However, in countries where large segments of the population cannot earn enough to feed themselves, currency debasement contributes to revolutions, not just the rise of populism.

For those that believe currency debasement is the appropriate way to escape a depression, keep in mind that the Great Depression provided a transition to World War II. Currency Wars fought in the first half of the 20th century tended to be a result of fiscal policy. For example, in 1925, the UK returned to the gold standard at pre World-War-I levels, although the UK could ill afford it. In 1931, Britain was forced to depart from the gold standard again. Japan suspended the gold standard in 1917, returned to it in early 1930, only to depart from it again in late 1931. In 1934, the U.S. dollar was devalued by 40% when an ounce of gold was officially priced at $35 an ounce, up from $20.67 an ounce. Exchange rates caught up with reality.

In today’s world, where major countries have free-floating exchange rates, monetary policies appear to be more pro-active rather than reactive. Either way, underlying fiscal or monetary policy have a profound impact on currency values, both in real (purchasing power) and relative (exchange rate) terms. Given unprecedented debt and deficit levels on the fiscal side, and aggressive central bank balance sheet expansion on the monetary side, we believe the term “currency war” is more than appropriate.

When told by Fed Chairman Bernanke that the gold standard prolonged the Great Depression, many feel as if monetary activism were a blessing rather than a curse. In our assessment, Ivory Tower economists are particularly apt at confusing cause and effect. The root causes of a depression are excessive debt, not currencies that are too strong. Currency debasement and expansionary monetary policies are attempts to socialize such debt, bailing out those that have taken on irresponsible debt burdens. But because governments tend to be in the group of those taking on excessive debt burdens, we are made to believe that such policy is for the greater good.

We respectfully disagree: currency wars destroy wealth. Currency wars have a disproportionate impact on the poor, as they don’t hold assets whose value is inflated in nominal terms and that could buffer some of the fallout. Central banks don’t cause real wars. But monetary policy has a profound impact on the social fabric. Abstract theories about how aggressive monetary action are the remedy to depressions ignores the heavy social toll currency wars have on people. For those that argue that the social toll of a depression is greater, we respond that the best short-term policy to address economic ills is a good long-term policy. We cannot see how currency wars can be good long-term policy.

What to do about Currency Wars

We can lament all we want, but ultimately, we are observers rather than instigators. We can be actors when it comes to our own wealth, seeking to protect it from the fallout of currency wars. We believe the best place to fight a currency war might be in the currency market itself, as there may be a direct translation from what we call the mania of policy makers into the currency markets. It’s not a zero-sum game, as different central banks print different amounts of money (that is, if one calls central bank balance sheet expansion money “printing”, even if no real currency is printed, but central banks purchase assets with fiat currency created on a keyboard). Equities may also rise when enough money is printed causing all asset prices to float higher, but one also takes on the “noise” of the equity markets: when no leverage is employed, equity markets are substantially more volatile than the currency markets.

Some call currency markets too difficult to understand. We happen to think that ten major currencies are much easier to understand than thousands of stocks. But nobody said it’s easy.

Calling it a race to the bottom does not give credit to what we believe are dramatically different cultures across the world. Gold may be the winner long-term, but for those who don’t have all their assets in gold, the question remains how to diversify beyond what we call the ultimate hard currency. To potentially profit from currency wars, one needs to project one’s view of what policy makers may be up to onto the currency space. And if there is one good thing to be said about our policy makers, it is that they may be rather predictable.

Labels:

Central Banks,

civil unrest,

Currency Wars,

Economy,

GIB,

Gold

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

@JamesGRickards Interview with The Voice of Russia

Reality Check: First Deputy Head of the Central Bank of Russia, Aleksey Ulyukaev warns that “We are now on the threshold of a very serious, I think, confrontational action, which is called, maybe excessively emotionally, currency wars”. Such artificial currency devaluation is a way “to a separation, a split into separate zones of influence, up to a very sharp competition, up to the world currency wars, which is definitely counterproductive,” Ulyukaev said. Are we on the verge of a currency war or we are already in a state of currency war?

James Rickards: We are already in a currency war. It began in 2010 when President Obama declared a goal of doubling U.S. exports in five years as part of his January 2010 State of the Union Address. Since then, the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank has used quantitative easing to cheapen the exchange value of the dollar both to promote exports and to import inflation as part of the Federal Reserve's efforts to target nominal GDP. However, Ulyukaev is correct when he says the effects of currency wars are divisive and counterproductive. We should expect increased inflation due to global monetary easing to fight the currency wars. It is also true that currency wars lead quickly to trade wars which can reduce global output and break the global economy into distinct trading and currency blocs. Many countries are now fighting the currency wars, but the U.S. is primarily responsible for this outbreak because the U.S. abandoned its sound dollar policy in 2010.

Reality Check: Sergey Glaziev, economy adviser of Vladimir Putin, recently said that "unconstrained monetary emission is a form of legalized aggression" because it allows some countries to use their "printing presses" to acquire real assets and at the same time finance their own "pyramids of debt". Do you agree with this view?

James Rickards: Yes. The U.S. can be aggressive in the currency wars because it maintains the leading reserve currency, the dollar, and it can print dollars at will to promote U.S. goals. Many other countries such as Brazil, South Korea, Taiwan, Mexico and others do not have reserve currencies and are put to the difficult choice of either maintaining a peg to the dollar, which causes inflation, or allowing their currencies to appreciate, which hurts exports. So we are seeing worldwide distress and dislocation because of the U.S. easy money policies. The same easy money policies are being pursued by Japan and the UK. The losers in the currency wars so far are the BRICS and other emerging markets. In the end, the entire world will lose because of inflation and a collapse of confidence in the paper money system.

Reality Check: How would you comment on the proposal made by David Kemper, Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer of Commerce Bancshares, Inc., and past President of the Federal Advisory Council of the Federal Reserve:

“I propose the Federal Open Market Committee’s next move be to take our central bank to a whole new level—a 2013 campaign that I call QE Cubed. Why not expand the Fed balance sheet exponentially, from its current $3 trillion to $33 trillion? Earning an extra 3 percent on another $30 trillion in bonds would allow the Fed to return an additional $900 billion to the Treasury—thus wiping out most of our federal deficit while avoiding actually having to do anything about current government spending”?

James Rickards: This view is consistent with that espoused by so-called Modern Monetary Theorists and is not far removed from views expressed publicly by President Charles Evans of the Chicago Fed and President Dennis Lockhart of the Atlanta Fed among others. This view is highly flawed because it assumes that money supply is a linear dynamic that can be dialed-up or dialed-down at will by central bankers in a predictable fashion with predictable results. In fact, monetary policy exists in a critical state dynamic. If it is pushed too far, it will "go critical" and catastrophically collapse in the same way that uranium can "go critical" and turn into a nuclear explosion when put into a certain configuration. Proponents of unlimited monetary easing are risking a sudden and unpredictable collapse in the international monetary system.

Reality Check: According to mainstream economists, if a country borrows money and stimulates consumption, this consumption is supposed to start a "virtuous cycle of growth" that is supposed to replace the "vicious cycle of deflation". During the last several years we've seen multiple massive stimulus programs but a "virtuous cycle" is nowhere to be seen. Why? Where are the "green shoots"?

James Rickards: This theory is based on Keynesianism and is widely discredited. So-called "stimulus" programs to not stimulate. They rob the private sector of valuable capital and waste it on politically motivated projects of little value.

Reality Check: Mainstream economists often say that the American currency system is designed in such a way that the US cannot go bankrupt and that the “dollar system” in which the dollar is the primary reserve currency of the world is irreplaceable. Do you think that the American leadership believes in the invulnerability of the dollar system?

James Rickards: American leaders do believe in the invulnerability of the dollar system, but they are misguided. The dollar system is based on confidence in policy. Once that confidence is lost, the dollar system can collapse very quickly as it almost did in 1980.

Reality Check: German Bundesbank began the process of gold repatriation from the New York Fed and Banque de France. Why are the Germans doing it now? Bill Gross of PIMCO tweeted that this is a sign of mistrust between the world’s central banks. Do you agree with this view?

James Rickards: Yes. As long as foreign gold is left in New York it can be confiscated by the United States in the event of an economic emergency. It is far more prudent for each gold power nation to keep most of its gold at home. A modest portion might be left in London or New York for trading purposes.

Reality Check: Several central banks, including Russia’s Central Bank have started gold acquisition programs. This situation presents a stark contrast to the situation when European central banks used to sell their gold. What has changed? Why is gold becoming popular with the central banks of the BRICS?

James Rickards: Gold was officially demonetized by the IMF in 1973 shortly after the U.S. broke with the Bretton Woods gold standard in 1971. What we are witnessing today is the slow remonetization of gold. This is evidenced by the following events:

* Russia has increased its gold reserves 50% in the past four years.

* China has increased its gold reserves over 200% in the past four years.

* Germany is requesting that its gold kept in New York and Paris be delivered to Frankfurt.

* Venezuela has repatriated its gold from London to Caracas.

* Azerbaijan has repatriated its gold from London to Baku.

* The Netherlands is considering repatriating its gold from New York, as are others.

* Vietnam, Philippines, Mexico and others have all made significant gold purchases recently.

This is a slow-motion run on the bank in terms of gold reserves. This can be expected to accelerate. There is no reason for a central bank to acquire gold or demand physical possession unless you believe that gold is money. If gold is money, then the implications for the price of gold based on the ratio of gold to paper money are an implied price of $7,000 per ounce, or higher.

Reality Check: Your book, Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisis talks about the currency wars phenomenon. A war is supposed to have a winner. Who will be the winners of the global currency wars?

James Rickards: The only winners in a currency war are those who refuse to fight. Countries that fight the currency wars will all lose due to inflation. Countries and currency blocs that do not fight the currency wars and maintain a strong currency and promote low corporate taxes and a sound business environment will be the winners. These winning countries include Germany and other members of the European Monetary System, Australia, Canada and Singapore.

Reality Check: If you were to pick only one asset class in which you could invest for the year 2013, what would it be and why?

James Rickards: Gold, because it performs well in conditions of inflation and deflation.

Labels:

Central Banks,

Currency Wars,

Gold

Tuesday, February 12, 2013

Currency War?

February 11, 2013 David R. Kotok, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer

“Currency War” is the latest hot title. It’s now on the front pages, triggered by the policy change in Japan. In only two months the Japanese yen has weakened about 15% against the US dollar.

Let’s reflect on this important development.

First, a simple case study. Suppose there were just two countries and just two currencies. Suppose country A decided to try to weaken its currency so it could sell more stuff at cheaper prices to country B, thus undercutting B’s domestic producers. B could resist by raising a tariff on the incoming stuff that A was trying to sell. Or it could retaliate by cheapening its own currency to counter the price differential. The first form of retaliation is a trade war; the second is a classic currency war. The economic history of the 1930s is replete with examples of each and combinations of both. History shows us that the results were disastrous for the global economy and led to a world war.

But is there a third alternative? What about the role of interest rates?

Suppose A announced that it wanted to weaken its currency by 5% against the currency of B. Furthermore, suppose A said it would do so over the course of one year. Then A proceeded to print more currency and use it to buy B’s currency, changing the exchange rate between A and B. Now let’s assume that B knew from earlier experience that retaliation would only lead to war, so B decided to do nothing. B also knew that in the longer term its citizens would benefit from a stronger currency, and B was confident enough and self-sufficient enough to allow A to cheapen itself for short-run gain. By doing nothing, B allowed the markets to make an adjustment. Suppose, also, that interest rates were not influenced by central banks’ actions. The markets would quickly price a 5% spread in the interest rate. At the one-year target maturity, the interest rate on debt denominated in currency A would be 5% higher than the rate on equivalent debt denominated in currency B. In a normal, clearing market, that is the way the adjustment occurs.

Japan is the leading candidate for the role of country A, given the policy changes announced and those still to come. The rest of the world is trying to figure out how to be a country B while being savvy enough to avoid deterioration into a trade war or currency war.

In our modern world there are more than two currencies. Four of them make up the bulk of the world’s reserves. The US does not hold much reserve in foreign currency; instead, the US dollar is the dominant reserve choice of the others. US dollars amount to about 60% of the world’s reserves and the euro about 25%. The yen and the pound are each about 4%. Add in a little gold, and you have tallied most of the world’s reserves. The rest of the countries are nice places to visit, but their currencies are bit players in terms of global impact.

Since November, one of the major (G4) currencies, Japan, has dramatically changed policy. Furthermore, Japan has directed its change in a way that causes another G4 currency, the euro, to strengthen. This action and ensuing reaction has triggered energetic discussion of a possible currency war.

Will we see one? Maybe. Are the currency moves we are seeing volatile and abrupt enough to ignite one? Yes.

The reason we’re on the brink of a currency war is that the central banks of the G4 have taken their policy interest rates to near zero. By doing so, they have collectively reduced the ability of market forces to adjust interest rates in response to the policy changes.

Let’s go back to our two-country example to see how this works. In our simplified model, interest rates were the adjusting mechanism. They were permitted to work when B decided not to engage in a policy change in response to A.

But what would have happened if the central banks of both A and B had taken their interest rates down to the near-zero boundary? And if, furthermore, A and B had committed to this policy because their respective economies were now attempting to recover from serious recessionary or deflationary damage? In this situation, interest-rate changes could no longer offset the exchange-rate mechanism. That is the outcome when the interest rates are managed by central banks. The normal market clearing forces cease to work. Instead, we get currency exchange-rate moves that deliver jolts to economies – bumps in a road that must be driven without shock absorbers. That is what happens when the mitigating effects of interest-rate changes are removed from the equation.

The world now finds itself in this position in response to the Japanese policy change. Here is a quick inventory of the G4.

Japan is committed to a weaker currency and to further central bank balance-sheet expansion. It is trying to get its economy to grow, and it is targeting an increase in inflation to 2%. Some forecasts expect the yen to reach 110 to 115 against the dollar within a year.

Meanwhile, the UK is trying to avoid a triple-dip recession. Expectations are that it, too, will engage in another round of monetary easing. We shall learn more as its new central bank governor gets established. With certainty, the UK will not tighten any time soon. Its short-term interest rate will hover at the near-zero boundary. And no one knows where the pound will trade as this next round of policy moves unfolds.

The US is likewise following its announced central bank balance-sheet expansion. The Federal Reserve affirmed that policy only a few days ago. Fed Vice-chair Janet Yellen reaffirmed it today. The Fed’s target for unemployment is 6.5%. (Currently the unemployment rate is 7.9%.) We have several more years before the Fed’s target rate will be reached. The Fed’s inflation target is 2.5%, and the US is operating at a lower inflation rate. Thus US policy is predictable for a while. US policymakers ignore the exchange value of the US dollar in making their decisions. They may talk about it, but FX is not the driver of decisions. As long as the US dollar maintains its current status as the dominant reserve choice, our nation will continue a practice of benign neglect with regard to our currency exchange rate.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the euro is strengthening in spite of all the difficulties in Europe. It is the G4 default choice because of the Japanese initiative and because the US and UK are in easing mode, while the European Central Bank has just reduced its excess reserves with a policy-changing transaction. Now ECB President Mario Draghi is worrying about his action being too much, too soon. We may see the euro trade up in strength against the others in the G4. That will compound Europe’s economic slowdown.

Note that in all cases interest rates remain very low, and the tendency of the central banks is to continue and to enlarge quantitative easing. We track that trend weekly at www.cumber.com . Also note that the economies we have discussed are not growing with any robustness, subjected as they are, in most cases, to higher taxes and anti-growth policies.

We believe that fears of a huge sovereign debt collapse are in error and misplaced. While they may eventually be realized, they do not loom in the near future. Meanwhile, currency volatility is likely to rise.

Our bond portfolios are slowly adjusting duration. We are using some strategic hedging of interest rates where that fits within the account objectives.

The central banks have the power to keep interest rates low for a prolonged period. They also have the power to influence the currency exchange rate. They do not have the power to do both at the same time unless it is a coincidental policy. It is going to be an interesting decade.

|

David R. Kotok, Chairman and Chief Investment Officer

|

Labels:

Central Banks,

Currency Wars,

Economy

Monday, February 11, 2013

Overvalued, Over bullish, Overbought, Rising Yields

Seems like we've been here before...

Six years ago today, with the S&P 500 around 1460 - having risen 20% without a correction for seven months - a handful of Wall Street's best and brightest joined CNBC's Larry Kudlow and Bob Pisani to discuss the Goldilocks economy, why the bears are wrong, and where the market is going next. Sometimes, we just need a reminder to snap us out of that recency bias... for example, Bob Pisani: "We have got a global rally going on... and the important thing is... there's a floor to the market - every time, for the last seven months, they sell the market down for 2 days, it comes right back."

Ralph Acampora: "I'm bullish, but I don't think I am bullish enough...there's new leadership"

Larry Kudlow: "Goldilocks kicks some more butt and the bears of the last four years are wrong... as they climb the 'wall of worry'"

Bob Pisani: "Transports have been rallying - as the disaster that the bears keep talking about hasn't happened... When you are in a global expansion like this, to sell...is foolish."

and our favorite:

Bob Pisani: "People who keep talking about this real estate bubble don't understand... there are 3 things that bring down real estate markets: 1) the economy falls apart, 2) liquidity is withdrawn, and 3) supply overwhelming market - NONE of that has happened."

...from Dr John...

“One ought to become concerned about risk when investors become convinced that it does not exist. There are certainly times when it appears easy, in hindsight, to make money in the stock market. The difficulty is in keeping it through the full cycle. The fact that over half of most bull market advances are surrendered in the subsequent bear doesn't sink in until after the fact. It's all fun and games until someone gets hurt.

“If the parents or the children of Wall Street analysts were to ask for wise investment advice, would the first thought of these analysts really be to encourage stock purchases at a multi-year market high, in a long-uncorrected and strenuously overbought advance, at a multiple of over 18 times earnings on unusually wide profit margins, with wages and unit labor costs rising faster than inflation, while interest rates are rising, bullish sentiment is unusually high, and corporate insiders are selling heavily? Would the potential for further gains in that environment exceed next inevitable correction by an amount that would make the net gains worth the risk? Would they encourage using trend-following systems in an overbought market, even though a decline to simple moving averages already implies substantial losses?

“Uncorrected market advances give a voice to the idea that ‘this time it's different.’ They invariably produce alternate valuation measures (like EBITDA multiples in the 90's, or price/forward operating earnings today) to replace the ones that suggest stocks are overvalued. These new-era arguments prevail despite the fact that the most recent evidence; the most recent market cycle; confirms the relationship between rich valuations and unsatisfactory long-term returns.

“No. We've been here before, and the consequences – though not always immediate – have invariably been bad. There is not a single instance in historical data since 1871 when the S&P 500 traded above 18 times record earnings and there was not a low a year or more later that erased every bit of advantage over Treasury bills. Not one.”

It’s All Fun and Games Until Someone Gets Hurt – February 5, 2007 Weekly Market Comment

Saturday, February 9, 2013

Venezuela devalues currency by 32% against the dollar

The widely expected measure ramps up the official exchange rate of the bolivar from 4.3 to 6.3 per US dollar.

It was announced after Vice-President Nicolas Maduro's return from Cuba, where he said President Hugo Chavez gave him instructions on the economy.

The leader has not been seen or heard in public since December, when he went to Havana for cancer treatment.

This is the fifth devaluation of the bolivar since Hugo Chavez' administration started controlling the exchange rate, in 2003.

The previous devaluation was in 2010.

Experts have long considered the bolivar overvalued and the move came as no surprise in the oil-based economy.

As oil exports are calculated in US dollars, a weaker bolivar should mean more cash for the government.

Strict controls to prevent currency going out of the country mean that dollars are normally hard to get in Venezuela, but in recent times this situation had become acute, says the BBC's Sarah Grainger, in Caracas.

Dollars have been trading at four times the official rate on the black market.

'Campaign money'

In a country that largely depends on food imports, the scarcity of dollars also led to shortages of products such as sugar and flour.

The new exchange rate is expected to address this situation.

But the measure is also expected to have an impact on the inflation, which has already been climbing.

The leader of the opposition, Henrique Caprilles, criticised on Twitter the fact that the government announced the devaluation on Carnival Friday in South America.

The opposition says the government has waited until after the elections to take the necessary steps in the economy.

"They've spent the money on the campaign, corruption and presents overseas," wrote Mr Caprilles, who lost the presidential elections to Mr Chavez last year.

Mr Chavez went to Cuba on 8 December to treat an undisclosed cancer and has not been seen or heard from since.

Mr Maduro recently said the president was "battling on" and had entered a new stage of treatment, after successfully finishing the post-operative phase.

Labels:

Currency Wars

Friday, February 8, 2013

This Time is Different...hmmm

| Displaying funny? View in browser. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

The McClellan Chart In Focus is a weekly technical analysis lesson. You have received this message because you have subscribed to this periodic email, to one of our market reports, or requested information on our services in the past. If you were forwarded this by a friend, you can subscribe here no strings attached. We don't share your email address with third parties or bombard you with marketing. Our mailing address is: McClellan Financial Publications P.O. Box 39779 Lakewood, WA 98496-3779 Our telephone: (253) 581-4889 Analysis is derived from data believed to be accurate, but such accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. It should not be assumed that such analysis, past or future, will be profitable or will equal past performance or guarantee future performance or trends. All trading and investment decisions are the sole responsibility of the reader. Inclusion of information about managed accounts program positions and other information is not intended as any type of recommendation, nor solicitation. We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone for any reason. The principals of McClellan Financial Publications, Inc. may have open positions in the markets covered. Copyright © 2013 McClellan Financial Publications All rights reserved. Feel free to forward this email to friends (intact). Please ask if you wish to re-publish our words or our charts. We are usually happy to accommodate. | |||||||||

|

Labels:

Central Banks,

Markets

Thursday, February 7, 2013

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

Tuesday, February 5, 2013

Monday, February 4, 2013

Transcript of Ray Dalio’s Comments at Davos

While most eyes were on a certain fight between two activist investors on Friday, another great investor also had some really interesting things to say. Bloomberg hosted a debate on the Global Economy at Davos with Ray Dalio and others. Here is the link to the video (if you’d like to watch the entire 50 minute panel) and below is a rough transcript of Dalio’s comments (with the times he was speaking):

8 minutes, 40 seconds: Are you concerned about inflation if you look at the way that we have all this cheap liquidity out there?

“I think the economy works like a machine and I think it’s important to understand how the machine works in order to answer that question. So if there is a transaction, you could pay with money or you can pay with credit. If you have money, that is making up for a contraction in credit. It’s not inflationary because the total amount spent in comparison to the total number of goods sold will determine the price.So when we’ve added money, we’ve made up for credit and that’s been fine. What’s happened now is that because of all the money that has been added to the system, there is a great deal of liquidity in the world. So there is money in corporations, in households. Liquidity is all over the place, a lot of it. And it has gone there because of monetary policy and it has also gone there seeking safety.That is changing on the margin. The returns of cash are terrible. So as a result of that, what we have is a lot of money in a place — and it needed to go there to make up for the contraction in credit — but a lot of money that is getting a very bad return. That, in this particular year, in my opinion, will shift. And the complexion of the world will change as that money goes from cash into other things.Now each region is very different, each set of circumstances. But the landscape will change I think particularly later in the year and beyond as those people who put their money there are receiving this bad return and feel an environment of safety [now] because the imbalances of Europe have largely been rectified. They have been rectified because the amount of borrowing is now consistent with the ability to fund that. And so the tail risks were taken off the table and that less risky environment is going to create that kind of a shift I think.”

11 minutes: Do you think we are seeing a credit bubble?

“There is a lot of liquidity, but the most fundamental laws of economics is you can’t have debt rise faster than income. You can’t have income rise faster than productivity and the long term growth will be dependent on productivity. And we have these cycles around productivity growth because of debt cycles. We don’t have a credit bubble because of the production of too much credit, but we do have a bubble in liquidity.There is too much liquidity and so bonds are a poor investment, they will have a poor return. Cash will have an even worse return, that’s assured. And that’s a bubble. Too much money in there. So the cash bubble exists, but we are reaching an equilibrium in terms of the debt growth.”

20 minutes, 20 seconds: (in response to another speaker’s comment)

“I think it is important to understand the adjustment that is happening is not just central banks feel there was a funding gap, the amount of money that can be lent and the amount of money that needed to be borrowed, there was a gap. And the central banks needed to come in and help fill that gap.What’s happened in the adjustment is that the amount of money that is being lent and borrowed has fallen a lot and with that depressions have historically occurred. So it is important to realize that when we go back to normalcy, normalcy [will not be] like the past. In other words those countries can’t spend the way that they have spent before. Equilibrium means a depressed economy. And what that means is the fundamental law is that we can’t raise debt faster than income from now on. And if we can’t raise debt faster than income we have to have a low debt growth and the issue will come to productivity.So the shift of the discussion is going to change. The shift of the discussion is now going to change in the economics of how do you become competitive. And so competition will be the discussion and I won’t go on there, but there are clear benchmarks for discussion about productivity and ultimately you can only spend what you produce.If you use the measures …literally what does it cost to have an educated person in France, the United States and China? Look at those comparisons and the cost of an educated person in these countries is multiples of the cost of an educated person in China and so when it comes down to it, there are going to be very big social questions. It’s going to be values of life. How long is vacation? How much savings? Very much quality of life types of questions. How much will there transfers of wealth? Productivity is going to be the question. There are clear benchmarks of productivity. I won’t go on, but we have a list of those things that correlate with 90 percent correlation with the outcome of the growth rate the next ten years. They are like a health index. If you look at that health index, you can go down that and compare it and those are going to be the drivers. Productivity, because the debt cycle will no longer be the main driver.”

27 minutes, 10 seconds: Ray are you concerned about currency wars?

“I’m not particularly concerned about currency wars. I also think central banks will play a much lesser role going forward. I think the ECB’s balance sheet will gradually taper off. The same thing with the U.S. So I think they will naturally recede. I think that their next move will be, as described, a move from liquidity to the purchases and then we have a shift. So I don’t think that is the issue. I think the shift of the cash, that massive amount of cash will be what will be a game changer…into stocks, into everything. It will mean more purchases of goods and services and financial assets. It will be into equities, it will be into real estate, it will be into gold, it will be into a lot of….just basically everything.”

39 minutes, 20 seconds: Audience question – What are your views on the Fed’s ability to shrink its balance sheet before it creates an inflation problem?

“Again I think it’s important to think of the economy as operating like a machine and everything is a transaction. So the amount of spending is what matters. Now spending can mean money or it can mean credit. If credit is picking up then money can decrease and so spending is the thing that matters. When it picks up, it will be incumbent on the central banks to reduce the amount of money so that the amount of spending is consistent with the productivity growth rate. And so I believe that that can be done as long as there is balance. As long as debt doesn’t rise faster than income, income doesn’t rise faster than productivity, and productivity then grows at a decent pace. That’s what matters.”

49 minutes, 25 seconds: Closing remarks

https://www.santangelsreview.com/2013/01/27/transcript-of-ray-dalios-comments-at-davos/“I think it is very difficult to talk about the world as a whole because conditions are very different. I think in the U.S., it’s a transition year. It’s one of those years that will go down in history as one you won’t even remember. It’s a transition in between cycles as we move from one to the other. I think in Europe, what we have achieved is the debt creation has been brought down to a level that is funding and that is a depression-like condition and that will now be an environment in which social pressures and political pressures will be difficult. And the importance there is not to have a pick-up in debt relative to income again and deal with it through productivity. I think in China they are in the other side of the cycle. The other side of the cycle is that debt is rising too fast relative to income and that is something that is the opposite side of the cycle and they will have to deal with it. So I think that those conditions are a landscape. They are transitions for all those countries.”

Labels:

Central Banks,

Currency Wars,

Economy,

Gold,

Investing

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)